Development of an artificial vessel that follows children's growth

14 January 2026

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a leading cause of mortality in children worldwide. This disease occurs because of abnormal heart formation before birth. In some cases of CHD, patients need to receive open chest surgery, during which their entire circulation is rearranged so that blood can flow normally. These patients can live long lives after the operation, but many of them develop complications later in life.

Gábor Závodszky, UvA Assistant Professor in computational biomedicine, explains: ‘During the operation, an artificial vessel segment is inserted. The patients have a lot of growth ahead of them, but these implants don't grow with them. So, as the patient reaches adulthood, the implant starts to pull on the surrounding tissues and vessels.’

Researchers of the MMD TechHub, led by Závodszky, are now creating an artificial vessel segment from a special material that enables the implant to grow with CHD patients, reducing their complications. They work closely with clinicians from the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) specialising in CHD. Závodszky: ‘The major driver of this project is that we're working on a device that has a good chance to be implanted in patients and help lives somewhere down the road.’

Unique and certified materials

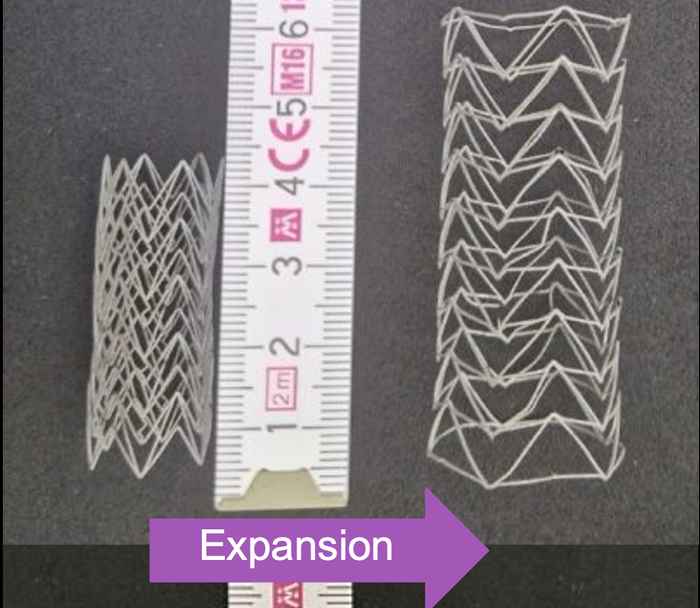

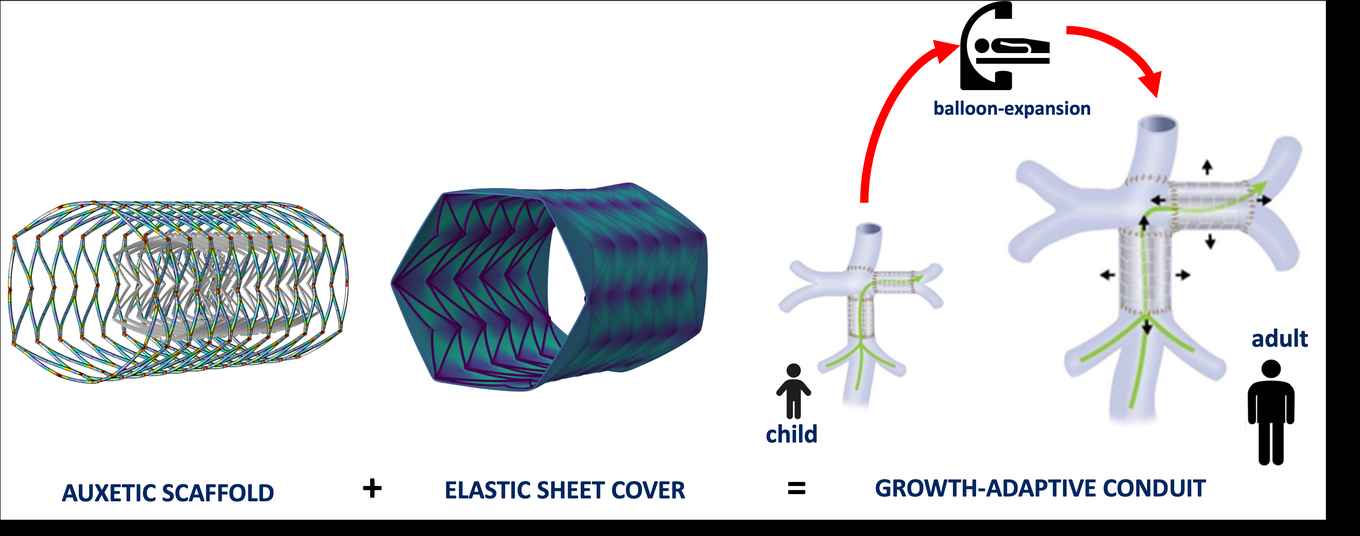

To make the implant, the researchers use auxetic materials, which have a counterintuitive property: When stretched in one direction, they expand instead of contract in the other direction. As a result, a cylindrical implant made from this material will increase in radius when stretched. If this expansion exactly matches the patient's growth in all directions, the implant doesn't need to be replaced.

The behaviour of auxetic materials is determined entirely by their geometry. Therefore, the researchers can make these implants from already certified materials, such as cobalt chromium for the metallic scaffold and polyurethane or silicone for the elastic cover. Clinicians can insert the implant using balloon catheters.

Závodszky: ‘The hope is that this research can be translated to an actual device very quickly, because no new techniques or materials are required. It's how you combine these materials that does the trick.’

Computational and clinical components

One major challenge of this research project is to find an implant design that will precisely match a patient's growth in all directions. For complex geometries, the required calculations become very difficult, making computational design a crucial part of the project. The researchers are developing optimization techniques that can gradually narrow down a large pool of possible shapes to just a few candidates. In addition to the growth of the implant, they take many other factors into account, such as whether the design can actually be manufactured.

Apart from the computational work, the project also has a strong clinical component. Therefore, clinicians from the LUMC, in particular Friso Rijnberg, are central to the project. They provide both medical data and expert insights in the disease. The researchers also work with Twente University, where they can test the implant in a chamber that simulates the blood flow of a patient.

Bringing to the market

To bring the implant to the market, the researchers also need to know the relevant regulatory processes, for example which types of evidence are required to show that the device is safe to use. They collaborate with a long list of companies to obtain this information and to manufacture the implant. Their main partner is the German device vendor AndraMed, and they also work closely with medical companies StarLight Cardiovascular and Ri.MED.

To verify the safety of the implant, animal trials are a necessary step. However, Závodszky set up the project to reduce the need for animal testing by putting more effort into simulations and using the test setup in Twente. Závodszky: ‘At the end of this project, I would be very happy if the animal testing phase would involve a record low number of animals. That's the goal that we try to achieve.’

The main driver of Závodszky and his team is to design this implant for children with CHD undergoing open-chest surgery. However, these auxetic materials may also have broader use. Závodszky: ‘We will also look into other permanently used artificial vessel segments or shunts. In diabetes, for instance, clinicians insert a shunt that remains in the patient for a long time, and the same problem arises: the shunt doesn't grow with the patient. We will also look into these applications in the future.’